Triple Spectre that Haunts Indian EV Policy

After setting an audacious goal of having 100% electric mobility by 2030, as announced by India’s Minister of Transportation in September 2017, we now find a situation of “electrifying confusion” regarding the goal post.

At the government level, different people are making contradicting statements and as always is the case in this country, that clear policy direction does not emerge.

Obviously, the lack of unified thinking among the government circle is quite visible when the Transport Minister says in January 2018 that the Electric Vehicle (EV) policy has been drafted by Niti Aayog and was awaiting for the cabinet approval. Then, he backtracks from this statement, a month later, saying that as such there was no need for EV policy. As a rejoinder, Vice Chairman of Niti Aayog suggests that India needs an EV policy, though the priority should be onto two-wheeler and public transportation. He further opines that as a nation our focus should be on this larger segment of electric mobility and not focus on cars.

There is more to this issue than meets the eye. In fact, the underlying issues for such backtracking and confusion seems to be the “Triple Spectre” which haunts India’s electric mobility odyssey.

Let us briefly look into these three factors.

- The Reality of Abatement of Carbon Footprint

Electric vehicles reduce pollution only if a high percentage of the electricity mix comes from renewable sources and if the battery manufacturing takes place at a site far from the vehicle use region. Industries which will emerge due to increased electric vehicle adoption may also cause additional air pollution.

One of the primary aspects of the audacious goal set for electric mobility was to deliver multiple co-benefits implying improved environment, energy security and renewable integration. Therefore, there is an imperative that there should be a domestic EV policy to improve competitiveness of electric vehicles.

“India can save 64% of anticipated passenger road-based mobility-related energy demand and 37% of carbon emissions in 2030 by pursuing a shared, electric, and connected mobility future”, according to a Niti Aayog-Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) report.

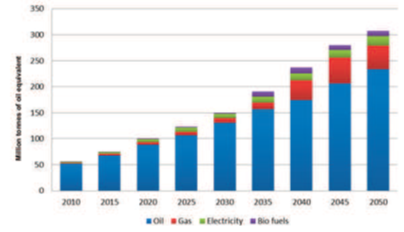

In a paper published by some IIM Ahmadabad researchers build various scenarios of EVs penetration. In a “business-as-usual” scenario, the overall transportation energy requirements increases nearly six fold between 2010 and 2050. The overall dependence on fossil fuels continues despite some diversification towards natural gas and bio-fuels. However, after 2020, electricity starts emerging as significant option, based on transportation for intercity passengers, freight movements, implementation of metro projects and diffusion of EVs (buses, cars, two/three wheelers). As per this model, the share of EVs in overall electricity demand rises from about 54% in 2020 to 67% in 2050.

In case of aggressive penetration of EV scenario, the overall demand of energy is lower because of the fact that EVs are more energy efficient. However, with addition of Low Carbon Society (LCS implies a global stabilization target of 2°C for global warming) coupled with EVs scenario, the energy demand further reduces. These are presented in the Figure 2 below:

It also means that if we have to achieve LCS goals, it is imperative that India’s EV policy document (as and when developed) must mandate use of renewable energy resources for charging of electric vehicles.

This would also help Indian renewable energy generation companies who are developing about 175 GW capacity including 100 GW from solar by 2022. Essentially, the fates of solar power and EVs in India are intertwined, provided that EVs have batteries that can offer a storage solution to India’s clean energy push.

Solar power generated during the day needs to be stored in batteries. The storage capability of EV batteries could help with grid balancing. This may mitigate a perceived risk that EV charging would lead to intermittent surge in electricity demand. Unless battery based storage facilities are created, there is a possibility of breakdown of India’s already stretched electricity distribution networks.

As seen in all the three cases presented by IIM scholars that EVs would lead to fresh demand for electricity. In fact, this could be a boon to our entire power sector as currently the lack of demand is weighing down the sector. Any uptake in demand for power will help improve the financial viability of currently stressed power sector projects.

Therefore, government is under dilemma whether to have a policy document that mandates only use of renewable energy for EV charging or to have those currently stressed power assets also have a play. Certainly, it is a tough decision to make. If the currently stressed power stations (which are largely fossil fuel based) get a play, then the role of reduction of carbon footprint would not be achieved for a country that still produces 75% of its electricity needs through fossil fuels.

Some may argue that the introduction of EVs would simply move the pollution of city roads to its hinter lands where power is generated.

- Impact on India’s Auto-component Industry

The Indian auto-component industry has experienced healthy growth over the last few years. It has grown to reach a level of Rs 2.92 lakh crore (US$ 43.52 billion) in FY 2016–17 and is further expected to grow by 8–10 % in FY 2017–18. As per an estimate by the Automotive Component Manufacturers Association of India (ACMA), the Indian auto-components industry is likely to reach a turnover of US$ 100 billion by 2020 backed by strong exports.

The auto-component industry accounts for almost 7 % of India’s GDP and employs as many as 25 million people, both directly and indirectly. A stable government framework, increased purchasing power, large domestic market, and an ever increasing development in infrastructure has made this possible.

Currently, the auto-component industry is deeply worried about the rapid transformation of the industry, i.e, from internal combustion engines (ICE) to EVs. Deeply concerned, ACMA represented to Niti Aayog in December 2017. The key points they lobbied were the current and project industry investments and the massive job losses. These are some of things that this country can ill afford. Therefore, government should take a more calibrated approach in quest of its rapid propagation drives for EVs to provide time to the industry to transit to making components and sub-assemblies or for this new segment of vehicles.

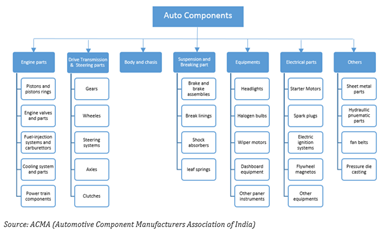

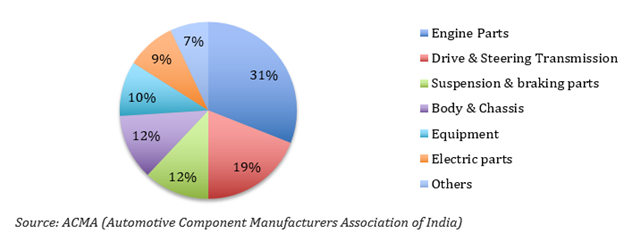

The industry’s plea seems to be genuine, given the fact that internal combustion engines which are used in most cars, have more than 2,000 moving parts, while an EV has about only 20, resulting in fewer breakdowns. Among the parts whose demand will dry up once EVs dominate in India are, the engines, transmission, aluminum castings, cylinder blocks and cast iron. The graphic below shows that taken together these constitute almost 50% of the industry. Such components will be replaced by electric motors which will run by batteries.

Yet another anxiety being expressed by the industry is that the ICE power-train contributes to over 60% of the employment generation in the auto component sector, and that a switch to 100% electric could impact up to 5.6 million jobs by 2025–26.

Following the global trend, the Indian auto-components industry is likely to follow OEMs in adoption of EV technologies. The global move towards EVs will generate new opportunities for automotive suppliers. The mass conversion to EVs may generate a US$ 300 billion domestic market for EV batteries in India by 2030.

The emergence of electric vehicles means a new ecosystem will have to be built and a lot of component manufacturers will have to adapt and transform to make the appropriate components and sub-assemblies for EVs.

As far as the adoption of EV technology is concerned, Indian automotive industry currently lags behind to its global peers by 7–8 years. This also a cause of concern, as it may erode competitive advantage of our local component industry, significantly.

Given the fact that this industry contributes substantially to GDP and job growth, it very preeminently is the poster boy of Indian manufacturing story. On one hand, the government is propagating various initiatives such as Make in India with an outlook to improve the employability opportunities for young population. On the other, they want rapid proliferation of EVs to meet the global targets of carbon footprint mitigation. To balance these opposing necessities, SIAM (Society for Indian Automobile Manufactures) has, in concurrence with the Niti Aayog come up with a via media that 40% of vehicles in India would be shifted to electric while vehicles used for public transport would be 100% shifted to electric by 2030.

This is another behind-the-scene issue that makes government diffident in bringing out a definitive policy on EVs. They are likely wait till checks and balances between two opposing key initiatives are thought through.

- Threat of Electronic Components Import Bill exceeding the Petroleum Import Bill

A major thought process behind India’s ambitious target of 100% electric mobility is to drastically reduce the crude oil import bill. According to a Niti Aayog-Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) report, adoption of EVs would result in a reduction of 156 Mtoe in diesel and petrol consumption by 2030. At $52/bbl of crude, this would imply a net savings of roughly Rs 3.9 lakh crore (approximately $60 billion) in that year.

The writings is on the wall — as with emerging technology, battery costs will continue to decline as manufacturing and the chemistry improves. Oil companies can reduce costs, but commodities do not see costs decline in the same way. Finite natural resources see costs rise as they become scarcer. The possibility that oil remains cheap indefinitely would only be because EVs destroy demand. As per a Bloomberg’s estimate, the EVs could capture 35 percent of the market by 2040, which would displace 13 mb/d.

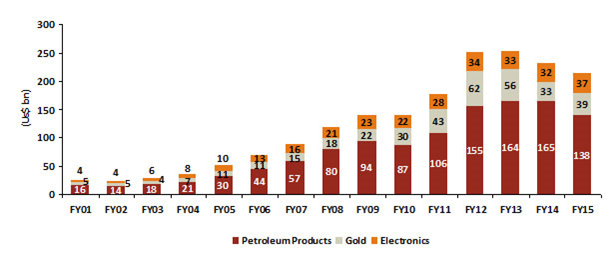

All this is fine in principle, but the following data, as per the ICICI Securities report, shows a very disturbing trend for India.

As per the above graph, petroleum products by far constitute the largest segment of India’s import bill. But, it is predicted to change soon as electronic goods bill will surpass the oil bill by 2020.

This is because, India is one of the largest growing electronics markets in the world with an estimated size of US$69.6 billion in 2012. With a CAGR of 24%, it is expected to surpass the US$400 billion mark by 2020. However, sharp growth in demand for electronic goods is unlikely to translate to higher domestic production, which is currently at US$32.7 billion and likely to cross US$104 billion by 2022. While the domestic industry will cater to only a fourth of this demand, India will still need to import goods worth US$300 billion, roughly equivalent to the country’s oil import bill. Till 2015, electronics imports at US$37 billion were the third highest import item next only to crude and gold.

Now, India is staring at an import nightmare of an unprecedented rise in proportion of electronic goods that can push the country into a spiral of high imports. This would necessarily entail higher external and internal borrowings and does not bode well for India’s economy in the long term.

India’s electronic goods production was inadequate to meet demand due to deficiency in skill level to compete with imported products. Hence, to meet the rising demand, India is heavily dependent on import of electronics goods from China, US and other South East Asian regions. If we dig deep, the main reason behind the rising import of electronic goods is shortfall in domestic production. Local production faces a substantial cost disadvantage constraining investment in plants and equipment, technology absorption, development capability and innovation.

There is a possibility of double whammy surrounding India’s EV program.This is because India does not have enough lithium reserves for manufacturing lithium-ion batteries. This could lead to a substantial change in the country’s energy security priorities, with securing lithium supplies, a key raw material for EV batteries, becoming as important as buying oil and gas fields overseas. So, on one hand the gains in reduction of oil import bill may get supplanted by securing lithium supply. On the other hand, in immediate run, the lithium batteries would again be imported from China and South Asian countries, leading to further bloating of India’s electronic good import bill.

Indian auto ancillary firms are worried about the EV story going the solar module way with most solar power developers sourcing modules and equipment from countries such as China, where they are cheaper.

The lack of battery manufacturing in India is a real problem. If India is not able to get its act together quickly enough to get into the manufacturing of all these new sunrise industries associated with EV ecosystem. Even on batteries, the same thing is going to happen. Already, China is making massive investments at massive scales, and we are still contemplating on it.

The delay in the EV policy is also possibility due to the fact to first get Electronics Manufacturing Policy in place to access from global networks of innovations and productions. This may result in indigenisation of sub-assemblies and key components for EVs. Over the years, local manufacturers faced barriers in the form of restrictive regulations and a largely poor implementation of past policies, which stymied investments in plants and equipment, technology absorption and innovations. This could be attributed to high cost of finance at 11–13% (cost of fund) against 2–4% globally, high power cost due to irregular power supply, etc. This, coupled with higher tax imposed by the Indian government, makes manufacturing of electronic products unviable in the country. All this has to change to make sure that the EV components (batteries, electric motors, electronic control modules) are made in India which will provide not only an alternative to auto ancillary industry, but also help in containing the electronic imports.

Conclusion

The slow down on getting the EV policy out is based on the fact that simultaneously India’s policy makers have to address issues that pertain to:-

1. Manage the reduction in carbon footprint by having calibrated introduction of renewable energy in charging infrastructure

2. Address the issues that are raised by auto ancillary industry through a gradual approach in introduction of EVs, so that the industry has reaction time to acquire the technology and build the production facilities to services OEMs entering into EV manufacturing.

3. Alleviate the lopsidedness of the electronic manufacturing in this country and providing fillip for manufacturing of batteries and other components in India, rather than resorting to massive imports.

No token or token has expired.

Deprecated: Function get_magic_quotes_gpc() is deprecated in /home1/silvege7/public_html/paradigmconsultant.com/wp-includes/formatting.php on line 4371